## loading libraries

library(tidyverse) # for data analysis and visualisation

library(here) # to organize files

library(praise) # for ocassional good vibes!Exploring numeric data (AE-3)

This application exercise is due on 20 Sept at 2:00pm.

Load packages, data

Graphical EDA

Plotting is an important skill to learn for effective data analysis.

Dotplot

- Look at the coding below and one at a time remove each of the dotsize, alpha, and stackdir from the code. What does each of these inputs do? How does each input impact upon the plot?

ggplot(data = diamonds) + # the data

geom_dotplot(mapping = aes(x = price), # plot of price

dotsize = 0.005, # make the dots tiny

alpha = 0.3, # less opaque

stackdir = "center") #Dotplot vs boxplot

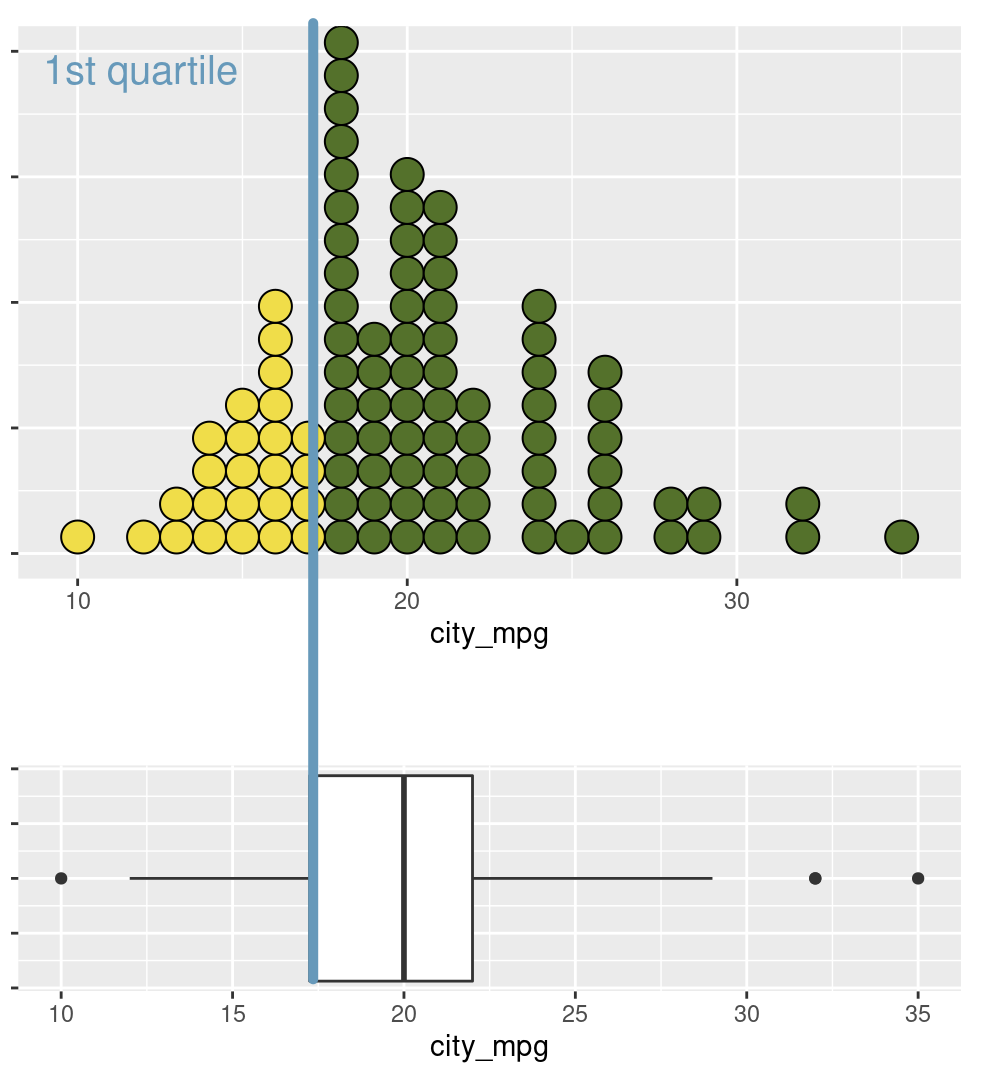

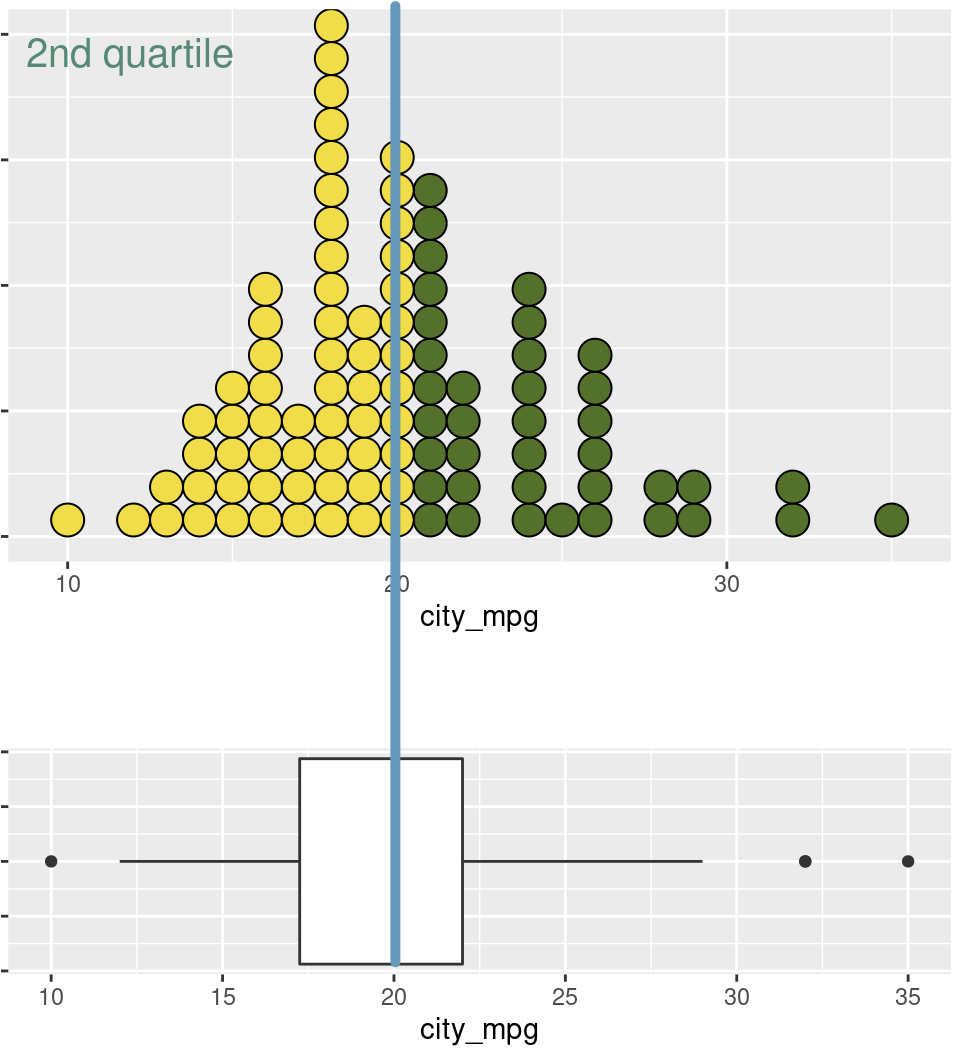

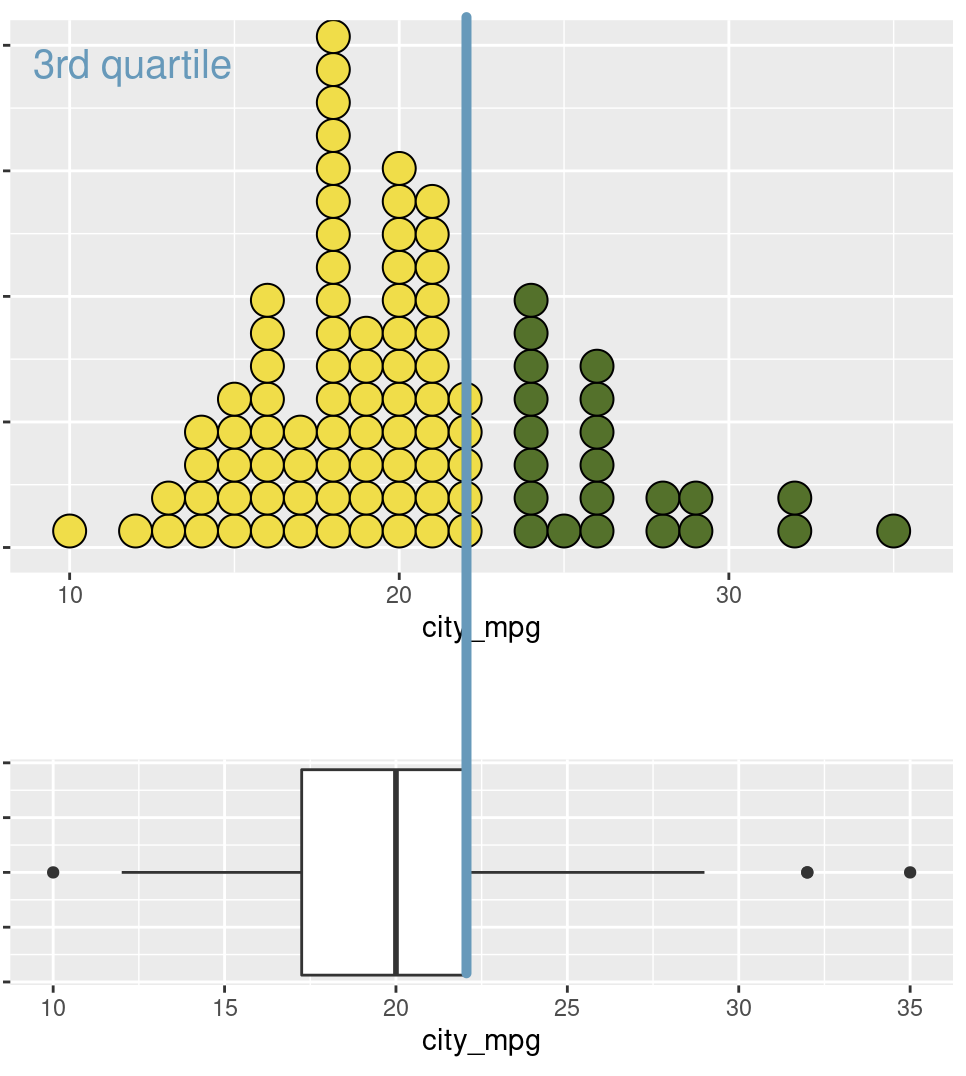

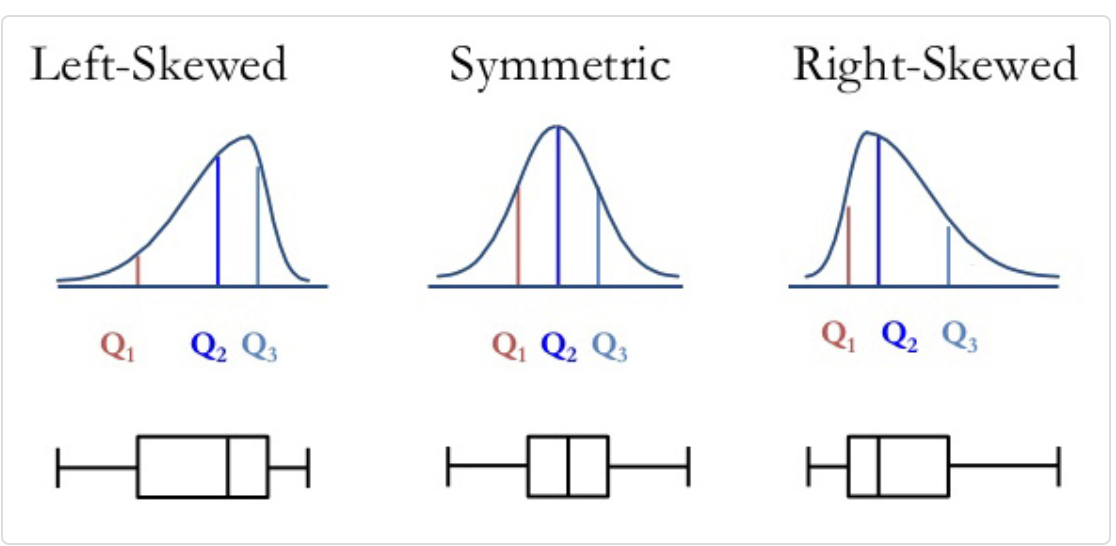

A boxplot provides summary information for the distribution of a variable. Here are some explanations (using different data) showing the purpose of the box portion of the boxplot.

The left line of the box is the quartile 1 (\(Q_1\)) or Q1

praise()The middle line of the box is the median (\(Q_2\))

The right line of the box is the quartile 3 (\(Q_3\))

Looking at the above plots, count the percentage of yellow dots in each of the dotplots. Is there anything interesting about these values?

Compare and contrast a dotplot and a boxplot? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each? Think carefully about bimodal data and which plot you would use to show that aspect of a variable. Also think about outliers.

Boxplots

- Draw a boxplot of the price data from the diamonds dataset.

ggplot(data = INSERT) + # the data

INSERT(aes(x = INSERT)) # the variableBoxplot descriptions

- Use the information above to describe the boxplot of price.

Interquartile range (IQR)

The IQR of a variable is the length of the box in a boxplot. \[ IQR = Q_3 - Q_1\]

praise()Density plot

ggplot(data = diamonds) + # the data

geom_density(aes(x = price), # plot of price

bw = 1) # plot of price- What does the “bw” input in the geom_density function do? What is an appropriate value of “bw” for this data?

ggplot(data = diamonds) + # the data

geom_density(aes(x = price), # plot of price

bw = INSERT) + # binwidth

facet_wrap(~clarity) # faceting- What does the above plot suggest about the prices of diamonds for all levels of the variable clarity?

praise()- Draw a density plot for each value of cut. Describe the distribution of diamond price for each value of cut.

ggplot(data = diamonds) + # the data

geom_density(aes(x = price), # plot of price

bw = INSERT) + # binwidth

facet_wrap(~INSERT) # facetingComputing summary statistics

It is not sufficient to only draw plots, we must also know typical values (measures of center) of the data and how spread out these values (measures of spread).

Measures of center

We use the summarise() function when we expect the result to be one number.

Mean

diamonds %>% # the dataset

summarise(mean = mean(price)) # function that is used to compute mean of price9, Now compute the means of the variables \(x\), \(y\), \(z\), and \(carat\). (hint: You will need to insert a code chunk for each of these variables.)

praise()Last class we learned about the group_by() and used it to compute conditional probabilities. Today we will use it to compare the means of different subgroups.

diamonds %>% # the data

group_by(cut) %>% # for each value of cut

summarise(mean = mean(price), # find the mean

median = median(price)) # and the median- Compare the average values of price for each level of the cut variable. Considering the distributions of price for each level of cut in question 8, is the grouped mean a good measure of center for each level of cut? Why or why not?

Median

- How would you find the overall median of price?

Measures of spread

Variance

R also computes measures of spread.

diamonds %>% # the data

summarise(var = var(price)) # find the varianceBesides the direct method above, we can also do this computationally, by using the definition and finding the mean, subtracting, and squaring, then dividing.

diamonds %>% # the data

mutate(

mean_price = mean(price), # mean of price

deviation = price - mean_price, # subtraction from notes

deviation_sq = deviation^2) %>% # then square it

summarise(

mean_sq_deviation = sum(deviation_sq)/ # sum them

(nrow(diamonds) - 1)) # divide by n - 1Run each line of code above and ensure that you understand how this computation was developed. This shows us how to find \(s_{price}^2\) directly.

Find \(s_{x}^2\), \(s_{y}^2\), and \(s_{z}^2\) both directly, and computationally: having

Rdo the computation. (hint: you will need to insert 6 code chunks)

praise()Standard deviation

Ralso computes the standard deviation \(s\) directly:

diamonds %>% # the data

summarise(sd = sd(price)) # find the sdCan you use the computational approach (finding the mean_sq_deviation) from above to find the standard deviation of price \(s_{price}\)? (hint: you will need to use the sqrt() operator)

IQR

- The \(IQR\) can also be computed directly or indirectly:

diamonds %>% # the data

summarise(

q1 = quantile(price, 0.25), # find Q1

q3 = quantile(price, 0.75), # find Q3

iqr = q3 - q1 # now the IQR

)Range

diamonds %>% # the data

summarise(

min = min(price), # find min

max = max(price), # find max

range = max - min # and range

)- Of all of the measures of spread, which do you think are sensitive to skewed data and outliers? Why?