Chapter 16: Statistical tests

STAT 1010 - Fall 2022

Learning outcomes

- Vocabulary: alternative hypothesis, null hupothesis, one-sided, two-sided hypotheses, and test statistic

- Understand the differences between a statistical test for proportions and for means.

- Recognize the different types of errors Type I and Type II when designing a test

- Distinguish between statistical and substantive significance

- Relate confidence intervals to two-sided tests

Does ESP exist?

Some people believe in the presence of Extrasensory Perception, or ESP. How could we prove whether it does or doesn’t exist?

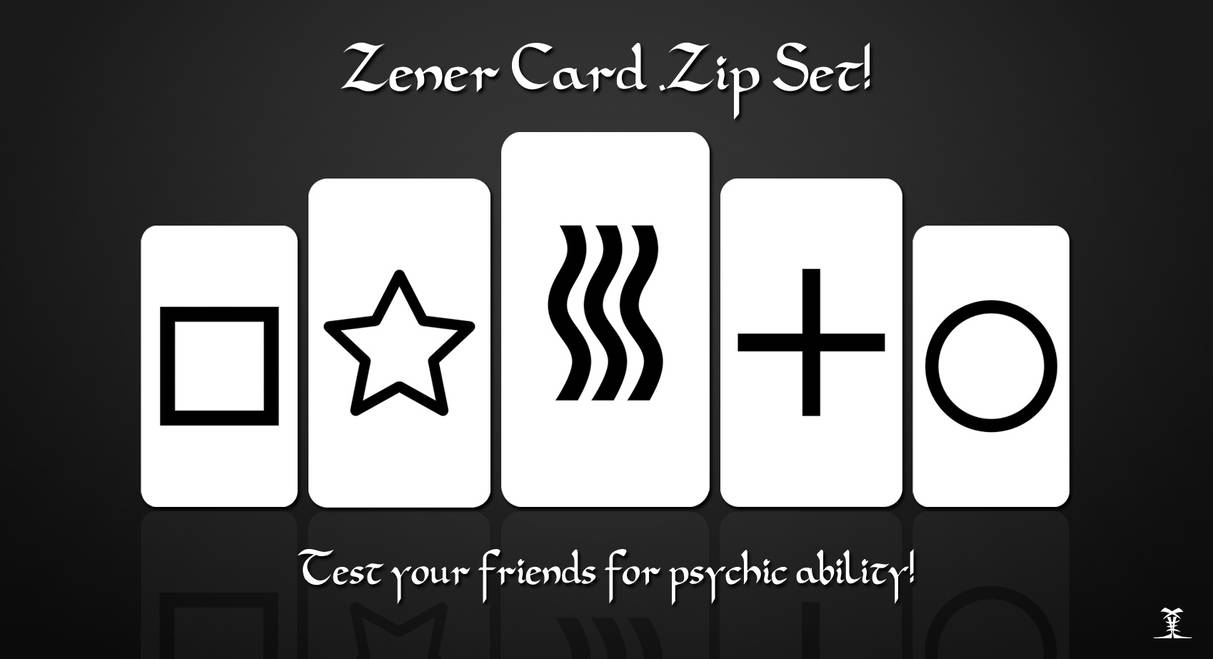

One test for ESP is with Zener cards.

Does ESP exist?

Since there are 5 cards, it would be possible to guess the correct card at random \(p=1/5\) times, or 20% of the time.

A person with ESP should be able to guess the correct card more often than 20%. But how much more often do they need to get it right for us to believe that ESP exists?

Statistical test

One way to determine something like this is to use a statistical test. A statistical test is a procedure to determine if the results from the sample are convincing enough to allow us to conclude something about the population.

Hypotheses

When we perform a statistical test, we set out our hypotheses before we begin. There are two hypotheses,

null hypothesis \(H_0\), a statement about there being no effect, or no difference.

alternative hypothesis \(H_A\), the thing that we secretly hope will turn out to be true.

ESP hypotheses

Thinking about the ESP experiment, we could use words to state our hypotheses

\(\begin{eqnarray*} &H_0:& \text{ ESP does not exist} \\ &H_A:& \text{ESP exists} \end{eqnarray*}\)

We could also write the hypotheses in terms of parameters,

\(\begin{eqnarray*} H_0: p \leq 1/5 \\ H_A: p > 1/5 \end{eqnarray*}\)

Hypotheses

- Hypotheses are always written about the population parameter (\(\mu\), \(p\), \(\mu_1-\mu_2\), \(p_1-p_2\)), never about the sample statistics (\(\bar{x}\), \(\hat{p}\), \(\bar{x}_1-\bar{x}_2\), \(\hat{p}_1-\hat{p}_2\)).

- The null hypothesis is the boring thing that we’re trying to gather evidence against

- The alternative hypothesis is the exciting thing that would make headlines

One and two sided hypotheses

- \(H_A\) has a \(>\) sign: upper tail, or “one-sided”

- \(H_A\) has a \(<\) sign: lower tail, or “one-sided”

- \(H_A\) has a \(\neq\) sign: both sides, or “two-sided”

Example 1

What are the null and alternate hypothesis for these decisions?

- A person interviews for a job opening. The company has to decide whether to hire the person

- An inventor proposes a new way to wrap packages that they say will speed up the manufacturing process. Should they adopt the new method?

- A sales representative submits receipts from a recent business trip. Staff must determine whether the claims are legitimate.

Example 1 solns

- $H_0 = $ Person is not hired

- $H_0 = $ Retain the current method

- $H_0 = $ Treat claims as legitimate. The employee is innocent until evidence to the contrary is found.

Past tests

Example 2

A snack-food chain runs a promotion in which shoppers are told that 1 in 4 kids’ meals includes a prize. A father buys two kids’ meals, and neither has a prize. He concludes that because neither has a prize, the chain is being deceptive.

- What is the null and alternative hypothesis?

- Describe a Type I error?

- Describe a Type II error?

- What is the probability that the father has made a Type I error?

Example 2 - solns

- \(H_0\) = chain is being honest; \(H_A\) = chain is not being honest

- Falsely accusing the chain of being deceptive

- Failing to realize that the chain is being deceptive

- Father rejects if both are missing a prize. \(P(neither has a prize) = (1 - 1/4)^2 \approx 0.56\)

Test statistic

In the previous example, we used probability to determine how likely it is to get two meals neither of which contain a prize. This process involves computing a test statistic (\(0.56\)).

Testing a proportion

To test a proportion, \(\hat{p}\), we must have a distribution with which to compare it. The distribution that we use is the distribution assumed in \(H_0\) we use \(p_0\) to denote this.

\[p_0 \sim N(p_0, \frac{{p_0}(1-{p_0})}{n}) \]

Testing a proportion - contd

Under \(H_0\), we find

\[z_0 = \frac{\hat{p} - p_0} {\sqrt{\frac{p_0(1-p_0)}{n}}} \]

Assumptions

- SRS and sample must be < \(10\%\) of population

- Both \(np_0\) and \(n(1-p_0)\) are larger than 10

Example 3

In the ESP example, we know that the population average for guessing ESP cards is 9 out of 24 cards. An interested participant took a training course to enhance their ESP. In the followup exam, they guessed 17 out of 36 cards. Did the course improve their ESP abilities?

Steps for a hypothesis test

- State hypotheses

- Determine the level of significance

- Check conditions

- Calculate test statistic

- Compute p-value

- Generic conclusion

- Interpret in context

Example 3 - solns

- \(H_0: p \leq 9/24\) and \(H_A: p > 9/24\)

- \(\alpha = 0.05\)

- Yes

9/24*36and(1-9/24)*36both > 10 - \(\hat{p} = \frac{x}{n} = \frac{17}{36} =0.472\)

- \(\begin{aligned} z_0 &= \frac{\hat{p} - p_0} {\sqrt{\frac{p_0(1-p_0)}{n}}} \\ &= \frac{0.472 - 0.375} {\sqrt{\frac{0.375(1-0.375)}{36}}} \\ &= \frac{0.0972}{0.0807} \approx 1.2 \end{aligned}\)

Example 3 - solns

1 -pnorm(1.2)or1- pnorm((17/36- 9/24)/sqrt((0.375*(1-0.375))/36))\(\approx 0.115\)- Since \(0.115 > \alpha = 0.05\) this is not significant.

- We fail to reject \(H_0\). The score does not provide evidence that the intervention improved ESP.

Testing a mean

To test a mean, \(\bar{x}\), we must have a distribution with which to compare it. The distribution that we use is the distribution assumed in \(H_0\) we use \(\mu_0\) to denote this. Because we don’t know \(\sigma\) we will once again use \(s\) from the sample

Testing a mean - contd

Under \(H_0\), we find

\[t = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu_0} {s/\sqrt{{n}}} \]

Assumptions

- SRS and sample must be < \(10\%\) of population

- If we do not know if the population is normal, \(n > 10|K_4|\)

Example 4

Let \(\bar{x} = 3281\), \(s = 529\), and \(n = 59\). Perform a hypothesis test that the sample comes from a distribution where the population mean is less than \(\mu_0 = 4000\)

Steps for a hypothesis test

- State hypotheses

- Determine the level of significance

- Check conditions

- Calculate test statistic

- Compute p-value

- Generic conclusion

- Interpret in context

Example 4 - solns

- \(H_0: p \geq 4000\) and \(H_A: p < 4000\)

- \(\alpha = 0.05\)

- Yes

- \(\bar{x} = 3281\)

- \(\begin{aligned} t &= \frac{\bar{X} - \mu_0} {s/\sqrt{{n}}}\\ &= \frac{3281-4000}{529/\sqrt{59}} \\ &= \frac{-719}{68.87} \approx -10.44 \end{aligned}\)

Example 4 - solns

pt(-10.44, df = 58)orpt((3281-4000)/(529/sqrt(59)), df = 58)\(\approx 3.07e-15\)- Since \(3.07e-15 < \alpha = 0.05\) this is significant.

- We reject \(H_0\). There is very strong evidence that the mean value is less than 4000.

Do extremists see the world in black and white?

Researcher Matt Motyl ran a study in 2010 with 2,000 participants. He wanted to determine if political moderates were able to perceive shades of grey more accurately than people on the far left or the far right. The p-value from the study was 0.01. Reject the null! Evidence in support of the idea that moderates can see grey better.

But then… he re-ran the study. This time, the p-value was 0.59. Not even close to significant.

What happened?!

Via Regina Nuzzo’s Nature article, Scientific method: Statistical Errors

Errors

There are two types of errors defined in hypothesis testing:

- Type I error, rejecting a true null

- Type II error, not rejecting a false null

Law analogy

In the US, a person is innocent until proven guilty, and evidence of guilt must be beyond “the shadow of a doubt.” We can make two types of mistakes:

- Convict an innocent person (type I error)

- Release a guilty person (type II error)

Extremists and black and white

Two options:

- the original study (p-value 0.01) made a Type I error, and the \(H_0\) was really true

- the second study (p-value 0.59) made a Type II error, and \(H_A\) is really true

or…

- maybe there were no errors made, just different studies found different things

Multiple testing

Because the probability of a Type I error is \(\alpha\), if you do many tests you will find significance in \(\alpha\) of them just by chance.

If you do 100 tests, you should expect to find 5 of them to be significant, just by chance.

This is the problem of multiple testing.

Multiple testing + publication bias

Okay, so \(\alpha\) of all tests show significance, just by random chance.

And things that look significant get published…

That means that a fair number of things that are published are actually false! This is pretty scary.

How to fix the problem

As a researcher:

- make sure your results can be replicated (like Motyl tried to do with the politics and grey study)

- publish code and data so others can study your work

As someone who reads about statistics:

- be skeptical about claims that are just one of many tests

- look for replication and reproducibility!

Reducing the probability of Type II error

In order to reduce the probability of making a Type II error, we can either

- increase the significance level

- increase the sample size

Statistical versus practical significance

Sometimes, you find something that is very statistically significant, but not practically significant.

For example, a revision program might increase final exam grades with \(p-value < 0.00001\), but it may only increase final exam grades by \(1\%\). This is statistically significant but not practically significant.

Context is important!

Confidence interval or test

These two are mostly interchangeable. However, tests only provide negative statements and does not give us much information about parameter values.