## install packages

library(tidyverse)

d.color <- diamonds %>%

filter(color == "D") %>%

select(carat)

j.color <- diamonds %>%

filter(color == "J") %>%

select(carat)

## 2 - sided test

## Alternative hypothesis: x != y

t.test(x = d.color, y = j.color, alternative = "two.sided")

## Alternative hypothesis: x < y by 0.1

t.test(x = d.color, y = j.color, alternative = "less", mu = .1)Chapter 17: Comparison

STAT 1010 - Fall 2022

Learning outcomes

- Recognize confounding

- Formulate hypotheses for comparing two proportions

- Perform a z-test for the difference between two proportions

- Perform a t-test for the difference between two means

- Distinguish between paired and independent samples

- Use a CI for difference to compare two proportions or two means

Different types of comparisons

From our last lecture, there are two courses that participants can take to improve their ESP abilities. One series of courses focuses on somatic training of the participant and the other on eye contact between the sender and receiver. For the purposes of this exercise, we let S be the event that a person took the first somatic course, and I be the event that a person took the first eye training course. This lesson will teach us how to assess these two courses. We will answer these questions:

- Does a higher proportion of people sign up for subsequent eye contact or somatic courses?

- Are the earning for the somatic group higher than those of the eye contact group?

Data

Let \(p_i = \text{the proportion of students who continue the series of eye contact training courses}\) and \(p_s = \text{the proportion of students who continue the series of somatic training courses}\). To demonstrate that somatic course is better than the eye contact, we want 2% more students to reenroll. The null hypothesis is \[H_0: p_s - p_i \leq 0.02\] means that enrollment in subsequent somatic courses does not meet this criteria. If the data rejects \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_A: p_s - p_i > 0.02\), this suggests the eye contact course is better.

Data - cont’d

There are a few ways that we can get data to explore these hypotheses:

- Experiment: random sample, assigns treatment, compares between treatments.

- Obtain random samples from two populations.

- Compare two sets of observations: can be problematic

Confounding

When levels of one variable are associated with levels of another the variables are said to be confounded.

In our example, perhaps we run a course Sedona, AZ where belief in ESP is high and people are likely to take the whole course. If the other was run in Phoenix, AZ this would not be the case. The belief in ESP in the location is confounded with taking subsequent courses.

Example 1

Which of the following appear safe from confounding and which appear to be contaminated?

- A comparison of two promotional displays using average daily sales in one store with one type of display and another store with a different type.

- A comparison of two promotional diplays using average daily sales in one store with one type of display on Monday and the other display on Friday.

- A comparison of two landscaping offers sent at random to potential customers in the same zip code.

Example 1 - solns

- Confounded by differences between the store, such as location or sales volume

- Confounded by differences in shopping patterns during the week.

- Free of confounding, though may not generalize to other zip codes

Two-sample \(z\)-test for proportions

\[ H_0: p_1 - p_2 \leq D_0 \]

The formula for standard error for \(\hat{p}_1-\hat{p}_2\) is

\(se(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2) = \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}_1(1-\hat{p}_1)}{n_1}+\frac{\hat{p}_2(1-\hat{p}_2)}{n_2}}\)

Assumptions

- No obvious lurking variable or confounders

- SRS condition, or independent random samples from two populations

- We need to check \(\begin{eqnarray*} n_1\cdot \hat{p}_1 \geq 10 \\ n_1\cdot(1-\hat{p}_1) \geq 10\\ n_2\cdot \hat{p}_2 \geq 10\\ n_2\cdot(1-\hat{p}_2) \geq 10 \end{eqnarray*}\)

Hypothesis test for a difference in proportions

\[ z = \frac{\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2 - D_0}{se(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2)}\]

Example 2

In the ESP example, spiritual groups decided to randomly assign members to either the somatic (\(n_s = 809\)) or eye contact group (\(n_i = 646\)). From those in the somatic group \(280\) re-enrolled, subsequent eye contact groups had \(197\). Perform a two sample \(z\)-test for proportions to determine if the enrollment in the somatic course was 2% more, on average, than that in the eye contact course.

Steps for a hypothesis test

- State hypotheses

- Determine the level of significance

- Check conditions

- Calculate test statistic

- Compute p-value

- Generic conclusion

- Interpret in context

Example 2 - solns

- \(H_0: p_s - p_i \leq 0.02\) and \(H_A: p_s - p_i > 0.02\)

- \(\alpha = 0.05\)

- Yes,

280/809*809and(1-280/809)*809both > 10 Yes,197/646*646and(1-197/646)*646both > 10 - \(\hat{p_i} = \frac{x_i}{n_i} = \frac{197}{646} = 0.305\) \(\hat{p_s} = \frac{x_s}{n_s} = \frac{280}{809} = 0.346\)

Example 2 - solns

- \(\begin{aligned} se(\hat{p}_s - \hat{p}_i) &= \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p}_s(1-\hat{p}_s)}{n_s}+\frac{\hat{p}_i(1-\hat{p}_i)}{n_i}} \\ &= \sqrt{\frac{0.305(1-0.305)}{646}+\frac{0.346(1-0.346)}{809}} \\ &= \sqrt{0.0003281 + 0.0002797} \approx 0.02465 \end{aligned}\) \(\begin{aligned} z_0 &= \frac{\hat{p_s} - \hat{p_i} - D_0} {se(\hat{p_s} - \hat{p_i})} \\ &= \frac{0.346 - 0.305 - 0.02} {0.02465} \\ &\approx 0.851927 \end{aligned}\)

1 - pnorm(0.851927) or \(\approx 0.197\)

- Since \(0.197 > \alpha = 0.05\) this is not significant.

- We fail to reject \(H_0\). The reenrollment in the somatic course is not significantly more than the reenrollment in the eye contact course.

Two-sample confidence interval for proportions

Sometimes we only want to estimate the difference, not determine if they is a statistically significant difference. We may not know which value of \(D_0\) to use.

- We can build 2 CIs (like we did here) to see if they overlap.

- We can build a CI for the difference between the two proportions

Math - two sample CI for props

\[ \hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2 - z_{\alpha/2} se(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2) \text{ to }\\ \hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2 + z_{\alpha/2} se(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2)\]

Assumptions

- No obvious lurking variables or confounders

- SRS condition

- Sample size condition

Example 3

In the ESP example, spiritual groups decided to randomly assign members to either the somatic (\(n_s = 809\)) or eye contact group (\(n_i = 646\)). From those in the somatic contact group \(280\) re-enrolled, subsequent eye contact groups had \(197\). Find the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the proportions who take subsequent courses on the somatic and eye contact group.

Example 3 - solns

- \(\begin{aligned} \text{lower bound} &= \hat{p}_s - \hat{p}_i - z_{\alpha/2} se(\hat{p}_s - \hat{p}_i) \\ &= 0.346 - 0.305 - 1.96 \cdot 0.02465 \\ &= 0.041 - 0.0483 \approx -0.0073 \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned} \text{upper bound} &= \hat{p}_s - \hat{p}_i + z_{\alpha/2} se(\hat{p}_s - \hat{p}_i) \\ &= 0.346 - 0.305 + 1.96 \cdot 0.02465 \\ &= 0.041 + 0.0483 \approx 0.0893 \end{aligned}\)

Interpretation

Since \(0 \text{ is in } [-0.0073, 0.0893]\) the difference is not statistically signficant at the \(95\%\) significance level. It is possible that the reenrollment rates for eye contact and the somatic course come from populations with the same proportion. We do not know which is higher, either could be.

If \(0\) is not in the \(95\%\) confidence interval, then the difference is significant and we can be \(95\%\) confident that the difference is between the lower and upper bounds. Any value in the region could plausibly be the difference in proportions between the two populations.

Two sample t-test

Instead of reenrollment levels, perhaps we’re interested in the differences in earnings from the two ESP course. In that case, we’ll need to use a two sample t-test:

\[ t = \frac{(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2) - D_0}{se(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2)} \]

Assumptions

- No lurking variables

- SRS condition

- Similar variances

- Each sample must exceed \(10|K_4|\)

In R

This computation is long and complicated, so it’s best done in R: t.test()

Since we only have summary data for the ESP example, we’ll show with the diamonds dataset. In this situation, we’ll ask if there is a relationship between carat (weight of the diamond) and color (D is best and J is worst). Which color has on average the largest diamonds?

\[ H_0: \mu_D - \mu_j \leq D_0\]

In R

In R

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: d.color and j.color

t = -41.811, df = 3683.7, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.5279915 -0.4806923

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

0.6577948 1.1621368

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: d.color and j.color

t = -50.101, df = 3683.7, p-value < 2.2e-16

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is less than 0.1

95 percent confidence interval:

-Inf -0.4844961

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

0.6577948 1.1621368 Interpretation

If the p-value is less than \(\alpha\) there is evidence against \(H_0\) and we can reject \(H_0\) in favor of the alternative.

“If the p-value is low then the null must go.”

2 - sided

There is extremely strong evidence that the mean carat for diamonds with the best color (D) is not the same as that for diamonds with the worst color (J).

alternative = “less”

There is extremely strong evidence that the mean carat for diamonds with the best color (D) is smaller by at least 0.1 then diamonds with the worst color (J).

But what is the magnitude of the difference?

CI for the difference between two means

\[ \bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2 - t_{\alpha/2} se(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2) \text{ to }\\ \bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2 + t_{\alpha/2} se(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2)\]

We use R to calculate. The assumptions are the same as those of the 2 sample t-test

\(se(\bar{X}_1 - \bar{X}_2) = \sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n_1}+\frac{s_2^2}{n_2}}\)

In R

Paired comparisons

We’ll circle back to this ESP example, but without the editing subsequent to class:

In the ESP example, an interested participant initially guessed 9 out of 24 cards and then took a training course to enhance their ESP. In the followup exam, they guessed 17 out of 36 cards. Did the course improve their ESP abilities?

What is the difference between these questions and why will a paired comparison give us more accurate solutions?

Another example

Certain people refused to get vacinated from COVID-19. To compare COVID infection rates it’s best to pair people who are vaccinated and not vaccinated but who also have similar education levels, incomes, and risk of infection. This hapenned last year in a UK government report.

Math

Given the paired data we find the differences (\(d_i = x_i – y_i\))

The \(100(1 - \alpha)%\) confidence paired t- interval is

\[\bar{d} \pm t_{\alpha/2, n-1} \frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}\]

Checklist: No obvious lurking variables. SRS condition. Sample size condition.

In R

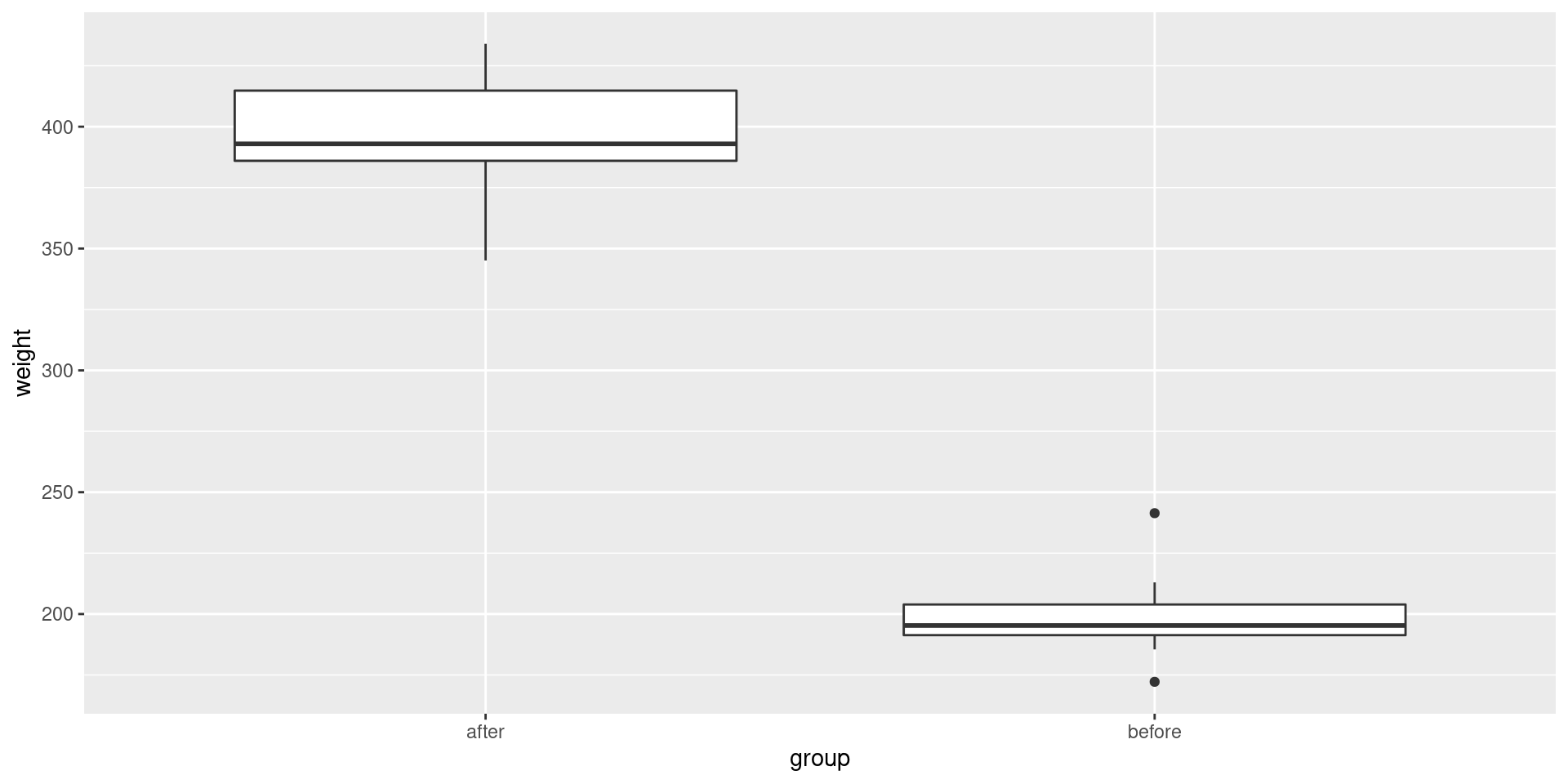

# Weight of mice before treatment

before <-c(200.1, 190.9, 192.7, 213, 241.4, 196.9, 172.2, 185.5, 205.2, 193.7)

# Weight of mice after treatment

after <-c(392.9, 393.2, 345.1, 393, 434, 427.9, 422, 383.9, 392.3, 352.2)

# A tibble

mice <- tibble(

group = rep(c("before", "after"), each = 10),

weight = c(before, after)

)

t.test(weight ~ group, data = mice, paired = TRUE)In R

Paired t-test

data: weight by group

t = 20.883, df = 9, p-value = 6.2e-09

alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

173.4219 215.5581

sample estimates:

mean difference

194.49 Plot

Interpretation

There is very strong evidence that the underlying population means of the mice before and after treatment are not the same. On average, the mice are much heavier after treatment.